By: Su Keles| Posted on August 25, 2022

Master your global communication skills (based on the 8 topics of the “The Culture Map”)

In this highly globalized environment, coming across different cultures and other work ethics is unavoidable. Professionals should be informed about those cultural differences to stay on top of their game and, more importantly, not offend their professional circle unintentionally.

Having a good grasp of different cultures is also crucial to understand how different markets operate. For instance, running the same content in every country is most likely not possible. A marketing strategy targeting Western cultures will not have the same intended effects on other cultures. It doesn’t matter where we work or who we are; we are all part of a global network where you must navigate highly different cultural scenarios to succeed. For instance, if you want to do business efficiently using multicultural platforms like Pharmaoffer, you will need a basic understanding of various cultures to create a good flow of communication.

Keeping culture in line with strategy is a fundamental challenge due to the continuously changing dynamics of markets and the need to alter and adapt the strategy. And the sad truth is that most managers who operate internationally in the business world have a limited understanding of how culture affects their work.

In this blog post, inspired by the bestselling book “The Culture Map “by Erin Meyers, we will dive into the cultural differences professionals can face in their work life. Even though there are so many perspectives we can take to interpret different cultures, we will focus on 8 categories; Communication, Feedback, Persuasion, Leadership, Decision making, |Trust, Disagreements, and Time Flexibility.

Communication is key

Countries with low-context cultures prefer a precise, simple and clear communication style, while high-context cultures prefer a more layered and nuanced one. If you’re from a low-context culture, a high-context communicator might appear secretive, lacking transparency, or just a bad communicator. But, if you’re from a high-context culture, a low-context communicator might appear condescending or inappropriately stating the obvious. The United States is the lowest-context culture in the world, followed by Canada and Australia, the Netherlands and Germany, and the United Kingdom. In a high-context culture like China or India, spelling out certain messages too explicitly is unnecessary. It can even be perceived as inappropriate.

Make Smarter API Decisions with Data

Access exclusive insights on global API pricing, export/import transactions, competitor activities and market intelligence.

For instance, if you send an inquiry to an American supplier and that person doesn’t have the answer right away, they will probably reply within 24 hours, saying something like, “We received your email and will give more information on Monday.” In other words, even if you have nothing to say, you should clarify in a low-context way when you have something to say. A lack of explicit communication signifies something negative. But, if you sent the same email to an Indian supplier, where lack of explicit communication is considered normal, you may not hear back from him for several days, then receive an email on Monday giving you all the information you need.

This also influences their style of work. For instance, the more low-context the culture, the more people tend to put everything in writing. Many high-context cultures, predominantly Asian and African, have a rich oral tradition in which written documentation is considered less necessary. So don’t be too shocked when you receive very short replies from Asian companies!

Feedback is the breakfast of champions.

Giving feedback, especially negative, is a sensitive topic, and not everyone takes criticism well. It can be made a lot worse if the person receiving the feedback believes the comment to be rude.

Countries with a direct negative feedback culture provide frank, blunt, and honest feedback. On the other hand, countries with an indirect negative feedback culture provide feedback in a more subtle, soft, and diplomatic way. Also, criticism is given in private, while in direct negative cultures, it can be delivered in front of people.

American culture is in the middle of the scale; the British are close but are slightly less direct with negative feedback than the Americans. Russians, the Dutch, and Germans are particularly big fans of offering frank criticism. Asian countries like India and China prefer subtle criticism.

For instance, expressing your opinions directly in a Dutch professional setting is always best. If you have some negative feedback, don’t sugar-coat it! However, if you find yourself surrounded by mainly Asian cultures, it might be better to think twice and reformulate before giving your feedback.

The art of persuasion

Persuasion is a crucial skill. Without the skill to persuade others to support your ideas, you won’t be able to make those ideas real. There are mainly two types of reasoning; Principles-first reasoning and Applications-first reasoning. The first one derives conclusions or facts from general principles or concepts; starting messages with summaries is common and theoretical discussions are avoided in the business environment. For the latter, general conclusions are reached based on a pattern of factual observations from the real world. They prefer to begin messages by building a theoretical argument before concluding.

To put it in simpler terms, people from principles-first cultures generally want to understand the reason behind their boss’s request before acting on it. On the contrary, applications-first learners will ask how they should proceed and tend to focus less on the reason behind the request.

But this still seems too theoretical; in more practical terms, applications-first thinkers like to receive hands-on examples upfront; they will learn from them. Principles-first thinkers also like practical examples but prefer understanding the framework’s basis before acting on it.

Anglo-Saxon cultures like the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand tend to fall into the application first reasoning. Most European countries, such as France and Russia, appear on the principles-first side of the scale. Asian countries also differ when it comes to reasoning. For example, Chinese people think from macro to micro, whereas Western people think from micro to macro. A good example is the difference in how Westerners and the Chinese write an address; the Chinese write in the sequence of province, city, district, block, and gate number. The Westerners do the exact opposite; they start with a single house number and gradually work their way up to the city and state.

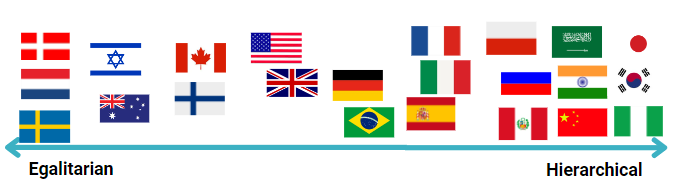

Leaders are learners

In egalitarian cultures, the ideal distance between the boss and the subordinate is low, a good boss is defined as someone who facilitates communication among equals, and communication is often not in hierarchical order. In hierarchical cultures, status is essential. A good boss is an authoritative director who leads from the front. So, the ideal distance between the boss and the subordinate is high.

Countries within the Nordic cultures, such as Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands, are known for their highly egalitarian culture at work. On the other hand, Russian and Asian cultures, like China and India, are known for their hierarchical mindset.

Professionals from countries with an egalitarian culture are more likely to move to action without getting the boss’s approval. They would, for instance, feel comfortable emailing or calling people from levels above or below themselves. This is the opposite of hierarchical cultures, where communication follows the hierarchical pattern, and people are more likely to wait for the boss’s approval before moving to action. So, don’t take it personally if your Indian or Chinese customers take longer to reply. They are probably busy double-checking with their boss!

How to put it into practice? When contacting professionals from Scandinavia, the Netherlands, and Australia, you could use their first names when writing emails. This is also largely true for the United States and the United Kingdom, but some regional exceptions exist. Or, let’s say that you are doing business with countries such as India, China, or Russia; it is better to communicate with the person at your level. So, if you are the boss, try to contact the boss.

The shot callers

In top-down cultures, decisions are made by individuals, and in most cases, the boss. In consensual cultures, decisions are made in groups with a common agreement. The United States and Germany are two important exceptions to the logical structure that egalitarian cultures tend to have consensus decision-making processes. In contrast, hierarchical cultures tend to practice top-down decision-making. While Americans perceive German organizations as hierarchical because of the fixed nature of the hierarchical structure, Germans consider American companies hierarchical because of their approach to decision-making since German culture places a higher value on building consensus.

American culture is one of a few outliers on the world map. Most cultures that are considered to be egalitarian also believe in consensual decision-making. For instance, the Dutch put a strong emphasis on both egalitarian leadership style and consensual decision-making. Similarly, from China or Korea, most hierarchical cultures are also top-down decision-making cultures.

But the remarkable exception is Japan, which is strongly hierarchical, yet remains one of the most consensual cultures in the world.

This clear paradoxical pattern can be explained by the fact that both hierarchical systems and consensual decision-making are deeply embedded in Japanese culture. They even employ a so-called “Ringi system” of decision-making, a management technique in which low-level managers discuss a new idea among themselves and reach a consensus before presenting it to managers of a higher level. The concept has developed over time. For instance, at Astellas, a Japanese pharma company, the Ringi process is managed by a software program.

There are several changes, such as proposals beginning at a mid-level of management, collecting group agreement, and then moving up to the next hierarchical level for further discussion.

Trust is everything

There are two forms of trust: cognitive trust and affective trust. Cognitive trust is based on your confidence in another person’s skills and reliability. Affective trust is based on feelings such as emotional closeness and empathy. In other words, you either trust using your brain or heart.

In task-based cultures, cognitive trust is built through business-related activities; they enjoy working together but stay within professional limits. But in relationship-based cultures, affective trust is created by sharing more personal moments and getting to know each other deeper.

Countries like the United States and the Netherlands operate with a task-based culture, while all BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) prefer working in a relationship-based culture.

So if you question and complain about why you have to spend so much time dining and socializing with potential clients instead of just signing the contract, you have to remember that in many cultures, the relationship is your contract. One wouldn’t do any good without the other.

Not all transactions are made through secure platforms such as Pharmaoffer, so if you plan to do business in person, make sure to be extra careful! Contracts do not hold the same significance in every country. And in some extreme cases, the only way you feel assured that you’ll be paid is to trust the other person.

Agreeing to disagree

In confrontational cultures, disagreement and debate are seen positively for the organization; open confrontation is appropriate and does not affect relationships. In cultures that avoid confrontation, disagreements are seen negatively, and open confrontation can appear rude. Countries like France, the Netherlands, Russia and Germany have a more confrontational culture, whereas Japan, China and India are on the side that prefers avoiding confrontation. The United States, like the UK, is in between these two extremes.

Some cultures are indeed more emotionally expressive than others. But emotional expressiveness should not be seen as the same as comfort in expressing open disagreement. People express disagreement openly in some emotionally expressive cultures, such as Spain and France. But, in other emotionally expressive cultures, such as Peru or India, people avoid open disagreement since there is a high chance it can badly affect their professional relationships.

A small tip: Americans consider a meeting good when a decision is made. The French consider a meeting good when diverse opinions and perspectives are put on the table and debated. However, in many Asian cultures, the real purpose of a meeting is to approve a decision that has already been made in informal discussions. So, the best time to express your disagreement is before the meeting rather than during the meeting in front of the group.

Is time on your side?

Running late to a meeting happens to the best of us, but your reaction to it can make a difference. For instance, if you live in a linear-time culture like Germany, Scandinavia, the United States, or the United Kingdom, you’ll probably call to let people know you will be late. If you don’t, you risk appearing rude and irresponsible.

And your thoughts on being late might differ if you are from a flexible-time culture such as the Middle East, Africa, India, or South America. In these societies, unpredictability is rooted in society, and as you fight traffic and other uncertainties during the day, delays are tolerated and considered normal.

We should also not forget that the particular country’s lifestyle heavily influences the time and scheduling culture. If you live in a strictly punctual country like Germany, you probably find things go according to plan. Trains are reliable, systems are dependable, and the rules are clear and enforced more or less consistently. This might not be the case for India, a dynamic and unpredictable country known for its chaotic traffic.

Using comparison platforms like Pharmaoffer can also allow you to ultimately do business with an organization that shares a similar linear culture to yours by presenting suppliers from different countries and giving you a choice to pick the most suitable one. But you don’t always have the chance to use similar platforms and choose for yourself, so focusing on your adaptation skills remains crucial.

Germanic, Anglo-Saxon and Northern European countries generally employ a more linear approach to time. Latin cultures (both Latin European and Latin American) tend to fall on the flexible-time side, with Middle Eastern and many African cultures being at the extremes. Asian cultures are dispersed on this scale; Japan is linear-time, while China and India prefer a flexible-time culture.

We hope this article will help you in your journey to discover the working etiquette of different cultures. At first, navigating different cultures can be challenging, but with the right mindset and information, it becomes a piece of cake. If you want to learn.” more, you should check Erin Meyer’s book “The Culture Map”.

Also, if you couldn’t find information on the country of your interest in this blog or book, don’t forget to check her website (link), where she lists all the countries mentioned in her Country Mapping Tool.

Check out all other blogs here!